What is Acute Myocardial Infarction?

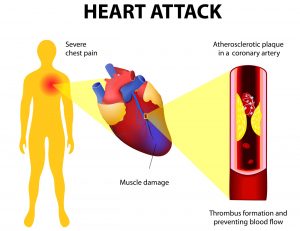

Acute myocardial infarction is a medical emergency and a life-threatening condition in which one of the arteries supplying blood to the heart becomes acutely, completely or partially obstructed.

This results in the interruption of blood flow to the corresponding region of the heart. The outcome may be temporary (reversible) or permanent damage—also known as myocardial necrosis—of the heart tissue supplied by the affected artery.

The longer the artery remains blocked, the greater the extent of myocardial infarction and the higher the likelihood of severe and irreversible damage to the heart muscle. The arterial network of the heart consists of the right coronary artery and the left main coronary artery.

Right coronary artery: Supplies blood to the inferior wall of the heart.

Left main coronary artery: Divides into two main branches:

Left anterior descending artery: Supplies the anterior wall.

Left circumflex artery: Supplies the posterior and lateral walls.

What are the symptoms of acute myocardial infarction?

Acute myocardial infarction presents with a range of symptoms that may vary in intensity and duration depending on the individual. Common symptoms include:

Chest pain: The most characteristic symptom, usually located in the center or left side of the chest, described as pressure, tightness, or heaviness. The pain is typically severe, persistent, and not relieved by rest or antianginal medications. It may last for >20–30 minutes or even hours, subside, and recur.

Radiating pain: May extend to the shoulders, arms (typically the left arm), back, neck, or jaw.

Shortness of breath: Can accompany or precede chest pain.

Excessive sweating: Occurs even at rest or in cool environments.

Nausea and vomiting: Common in some patients.

Weakness and dizziness: May be sudden and severe.

Cold sweat: Often accompanies chest pain.

Sense of anxiety: Intense anxiety or fear may occur along with other symptoms.

Atypical symptoms

In certain populations—especially women, elderly individuals, and those with diabetes—symptoms may be atypical, such as shortness of breath, upper abdominal (epigastric) burning or discomfort, and numbness or discomfort in the neck, jaw, limbs, or back.

What causes acute myocardial infarction?

Acute myocardial infarction is usually the result of underlying coronary artery disease, which is characterized by atherosclerotic plaques in the coronary arteries formed by the accumulation of cholesterol, inflammatory cells, and other substances in the arterial walls.

Atherosclerotic plaque and thrombosis

When an atherosclerotic plaque ruptures, its contents are exposed to the bloodstream, triggering the clotting process and resulting in thrombus formation. The thrombus may block the artery and halt blood flow to the heart.

Contributing factors and risk factors include:

Hypertension: Damages arteries and accelerates atherosclerosis.

Hypercholesterolemia: Promotes plaque formation.

Smoking: Damages vessels, increases oxidative stress and inflammation, and reduces oxygen delivery.

Diabetes: Leads to high blood sugar and vascular damage.

Obesity: Associated with hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes.

Physical inactivity: Increases risk for cardiovascular disease.

Stress: Raises blood pressure, inflammatory markers, and stress hormones that harm the myocardium.

Family history: Genetic predisposition to cardiovascular disease.

Age and sex: Risk increases with age; men have higher risk earlier, women post-menopause.

How is acute myocardial infarction treated?

The treatment of acute myocardial infarction requires immediate and coordinated medical intervention in order to reduce damage and injury to the heart muscle and improve overall cardiac function and performance. Management includes a range of both immediate and long-term strategies.

The most critical intervention involves restoring normal blood flow, which includes the prompt opening and revascularization of the occluded coronary artery. Early reopening of the artery and the subsequent restoration of normal blood flow reduces the extent of the infarction, the degree of systolic dysfunction of the heart, and improves the patient’s overall prognosis. There are two main methods of revascularization.

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) involves the use of a balloon catheter to reopen the artery by dilating the blockage, and is often followed by the implantation of an intracoronary stent to maintain arterial patency and prevent restenosis.

Alternatively, in cases where primary PCI is not feasible, thrombolytic therapy is administered intravenously using specialized thrombolytic agents that dissolve the clot responsible for the acute occlusion, resulting in the restoration of normal coronary blood flow.

This therapy is most effective when administered within a few hours of symptom onset. Subsequently, the patient may undergo diagnostic coronary angiography and therapeutic PCI.

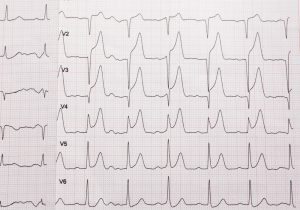

Additional measures following hospital admission include the immediate assessment of vital signs, such as blood pressure, heart rate, and oxygen saturation.

This is crucial for understanding the severity of the condition and adjusting the therapeutic strategy accordingly (some patients may present with immediate cardiovascular collapse or cardiogenic shock, a condition that requires mechanical support of respiratory and cardiac function).

In cases of low oxygen saturation, oxygen is administered to ensure adequate myocardial oxygen delivery and reduce the extent of injury to the heart muscle due to hypoxia (oxygen deprivation) resulting from the arterial occlusion.

Analgesic therapy is also provided with intravenous opioids to relieve pain and discomfort. Pain control is important as it reduces cardiac stress and improves symptom relief.

Medications such as aspirin, clopidogrel, and newer generation antiplatelet agents such as prasugrel and ticagrelor, as well as glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, are administered to inhibit blood clotting and prevent new thrombus formation. Drugs that reduce the cardiac workload, such as beta-blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, help lower blood pressure and overall cardiac workload.

These medications reduce the heart’s oxygen demand, thereby minimizing the extent of myocardial injury and improving long-term cardiac function.

After the initial treatment, patients typically require continuous monitoring and long-term pharmacological therapy to prevent future episodes and improve heart health. Statins are used to reduce cholesterol levels and prevent the progression of coronary artery disease and related cardiovascular events.

Complete recovery also involves lifestyle modifications such as improving diet, increasing physical activity, and quitting smoking. A coordinated approach to these therapeutic strategies contributes to improved heart health and reduced risk of future cardiovascular events.

What complications may arise after acute myocardial infarction?

Following an acute myocardial infarction, several complications may arise that affect overall heart function and the general health of the patient. These complications may include mechanical complications such as cardiogenic shock, papillary muscle rupture, myocardial dysfunction with severe mitral valve regurgitation, and rupture of the interventricular septum (VSD) or other walls of the left ventricle. Additionally, serious malignant arrhythmias such as ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation, and subsequent cardiac arrest and sudden cardiac death may occur.

In cardiogenic shock, the heart is unable to pump sufficient blood to meet the body’s oxygen demands, resulting in low blood pressure, reduced perfusion to vital organs, and ultimately multi-organ failure.

This condition requires immediate mechanical support of cardiac function through the use of devices such as the intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP), the Impella ventricular assist device, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO).

Other mechanical complications, such as papillary muscle rupture with consequent mitral valve regurgitation, and rupture of the interventricular septum or other parts of the myocardium, often require emergency surgical intervention to immediately repair the mechanical defect. Mortality remains extremely high in these cases.

Regarding arrhythmias, they are common complications after myocardial infarction, and their management and prevention include the administration of antiarrhythmic medications such as beta-blockers and amiodarone.

In cases where these arrhythmias are accompanied by hemodynamic instability, immediate intervention with electrical cardioversion and defibrillation is required to restore normal heart rhythm.

Chronic ischemic cardiomyopathy and heart failure with severe systolic dysfunction of the heart muscle may also occur after a myocardial infarction, leading to chronic impairment of the heart’s ability to pump blood effectively.

This may result in chronic heart failure, which requires long-term pharmacological treatment and other interventions to prevent sudden cardiac death, including the implantation of cardiac resynchronization therapy devices and defibrillators (biventricular ICDs) and significant lifestyle modifications.